Energy Balance Over Time: Short-term vs Long-term Patterns

Energy Balance as a Dynamic Process

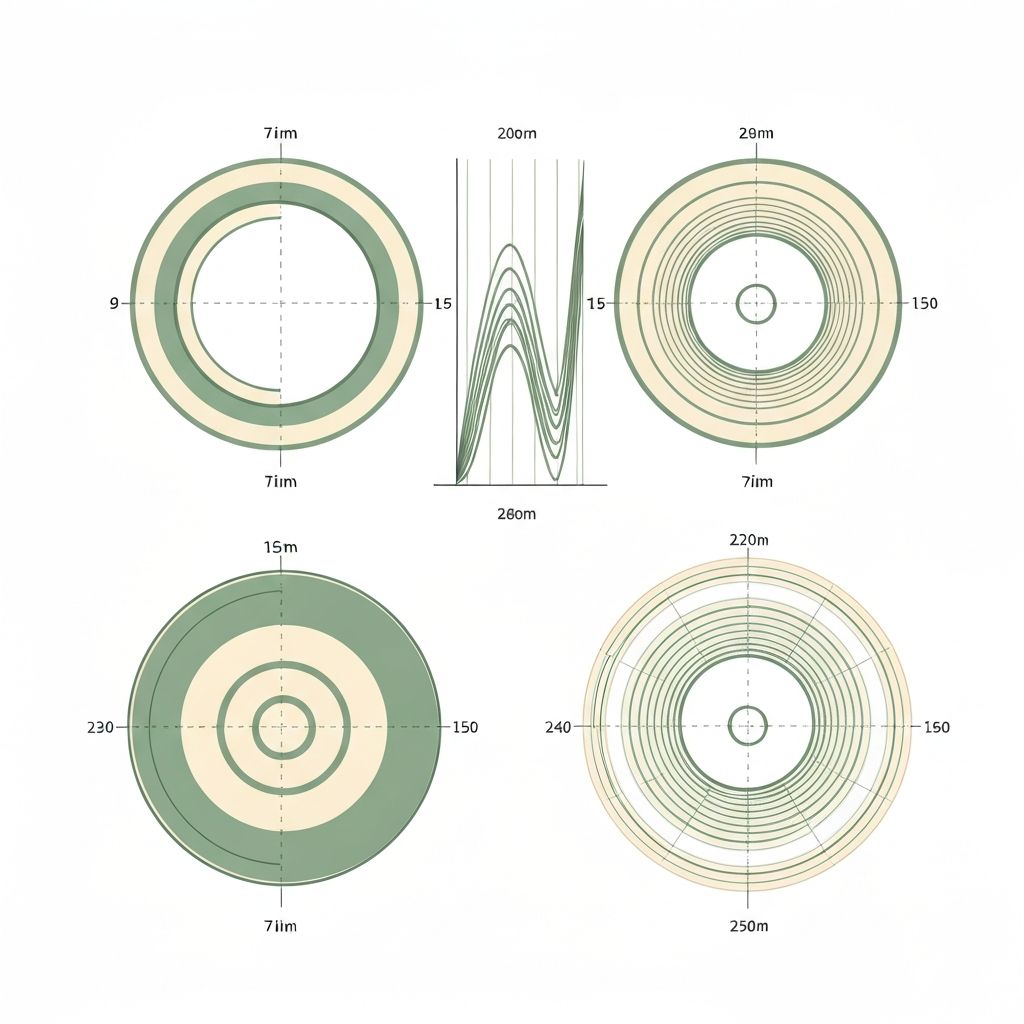

Energy balance is not a static state but a dynamic process occurring across multiple time scales. While the fundamental principle remains constant—weight changes result from cumulative imbalances between intake and expenditure—the timeframe over which we observe energy balance dramatically affects interpretation of the system. Understanding how energy balance operates over different time periods provides perspective on physiological adaptation and weight stability.

Short-term Energy Balance (Hours to Days)

On hourly and daily timescales, energy balance fluctuates considerably:

- Daily intake variation: Food consumption varies day-to-day due to appetite, schedule, social factors, and other influences. A person might consume 2000 kcal one day and 2300 kcal another

- Daily expenditure variation: Energy expenditure changes based on activity level, sleep quality, environmental temperature, and other factors

- Weight fluctuation: Body weight naturally fluctuates 1-3 kg daily due to fluid retention, food volume, digestive content, hormonal changes, and other physiological processes unrelated to energy balance

- No net change expected: Individual days rarely show perfect balance between intake and expenditure, and this is entirely normal and expected

Short-term energy imbalances—even substantial ones—do not determine long-term weight changes. Consuming 500 kcal excess one day does not result in permanent weight gain; consuming 500 kcal deficit one day does not result in weight loss. The body exhibits buffering mechanisms that smooth out day-to-day fluctuations.

Medium-term Energy Balance (Weeks to Months)

Energy balance becomes more predictable over weeks and months:

- Cumulative patterns emerge: Averaging intake and expenditure over several weeks reveals true patterns beneath daily noise

- Weight trends stabilize: While weight still fluctuates daily, directional trends become apparent when viewed across weeks

- Metabolic adaptation begins: If energy intake drops substantially below expenditure, the body initiates adaptive responses within weeks, including reduced thermic effect of activity and potential NEAT reduction

- Predictable changes: A sustained 500 kcal daily deficit typically produces approximately 0.5 kg weight loss weekly, though individual variation is substantial

Long-term Energy Balance (Months to Years)

Over extended periods, long-term energy balance determines weight stability or change:

- Weight set point concept: While controversial, research suggests the body may defend weight around a physiological set point through metabolic and behavioural adjustments

- Metabolic adaptation: Extended periods of energy imbalance trigger adaptive responses. Sustained undereating reduces metabolic rate; sustained overeating slightly increases it

- Behavioural adaptation: Over time, people unconsciously adjust activity and eating based on weight changes and energy balance state

- Weight stability: Most people maintain relatively stable weight over years, suggesting long-term average intake approximately equals long-term average expenditure

Metabolic Adaptation Mechanisms

When energy balance deviates from neutral for extended periods, the body activates several adaptive mechanisms:

Metabolic Rate Changes

Sustained energy deficit triggers metabolic slowdown—basal metabolic rate and thermic effects decrease modestly. The magnitude is typically 5-25% depending on deficit severity and duration. This adaptation partially offsets deficit effects.

Activity Changes

Energy deficit may reduce NEAT through unconscious activity reduction or reduced fidgeting. Overeating may increase NEAT as the body expends energy through increased spontaneous movement, partially offsetting surplus.

Hunger Changes

Prolonged undereating increases hunger signals, driving increased appetite. Overeating suppresses hunger signals. These adaptive changes in appetite hormones may promote return to baseline weight through reduced or increased intake.

Temporal Dynamics and Weight Prediction

Understanding temporal scales helps explain weight changes:

- Initial rapid changes: Weight changes during the first week of altered intake often exceed predictions because they include water loss and digestive content changes rather than solely tissue changes

- Adaptation plateau: After weeks of sustained imbalance, metabolic adaptation slows weight change below initial rates despite continued deficit

- Long-term stability: Over many months, metabolic adaptation and behavioural responses may offset sustained energy imbalance, establishing new weight equilibrium

- Individual variation: Adaptation rates vary between individuals; some show rapid metabolic adjustment, others minimal adaptation

Research on Long-term Energy Balance

Studies examining energy balance across time reveal interesting patterns:

Energy deficit or surplus produces expected weight changes following simple mathematics. Metabolic adaptation is minimal over this timeframe.

Metabolic adaptation becomes apparent; weight change slows relative to initial rates despite continued energy imbalance. Individual variation increases.

Weight often stabilises despite continued energy imbalance, suggesting adaptation mechanisms offset deficit or surplus effects. Maintenance of intentional weight changes requires sustained intake adjustment.

When energy imbalance ends, weight often returns toward previous levels through combination of reduced adaptation and returning to previous intake patterns.

Implications for Understanding Energy Balance

Viewing energy balance across multiple timeframes provides important perspective:

- Daily variation is normal: Day-to-day fluctuations in intake and weight are expected and do not indicate failure or success

- Weekly and monthly trends matter: Meaningful patterns emerge only when averaging across weeks, smoothing daily variation

- Adaptation is real: Sustained energy imbalance triggers adaptive responses that modify metabolic rate, activity, and appetite

- Weight regulation mechanisms exist: The body actively defends weight rather than passively responding to energy balance

- Individual differences persist: While fundamental physics governs energy balance, physiological adaptation and individual differences create substantial variation in how individuals respond to energy imbalance

Weight Stability Over Time

Most people maintain relatively stable weight over years despite short-term intake and activity variations. This stability suggests long-term energy balance—average intake approximately equals average expenditure. Understanding this reflects complex regulation involving metabolic, behavioural, and hormonal mechanisms rather than simple passive energy balancing.