Thermic Effect of Food: How Digestion Uses Energy

What Is the Thermic Effect of Food?

The Thermic Effect of Food (TEF), also known as diet-induced thermogenesis or postprandial thermogenesis, represents the increase in energy expenditure that occurs after consuming food. Simply put, your body expends energy digesting, absorbing, and processing the nutrients from food. This energy cost of processing nutrients is measurable and varies depending on what you eat.

TEF typically accounts for approximately 8-15 percent of total daily energy expenditure. While this seems modest compared to basal metabolic rate or physical activity, it remains a meaningful component of overall energy expenditure. The amount of energy expended during digestion varies significantly based on the macronutrient composition of meals.

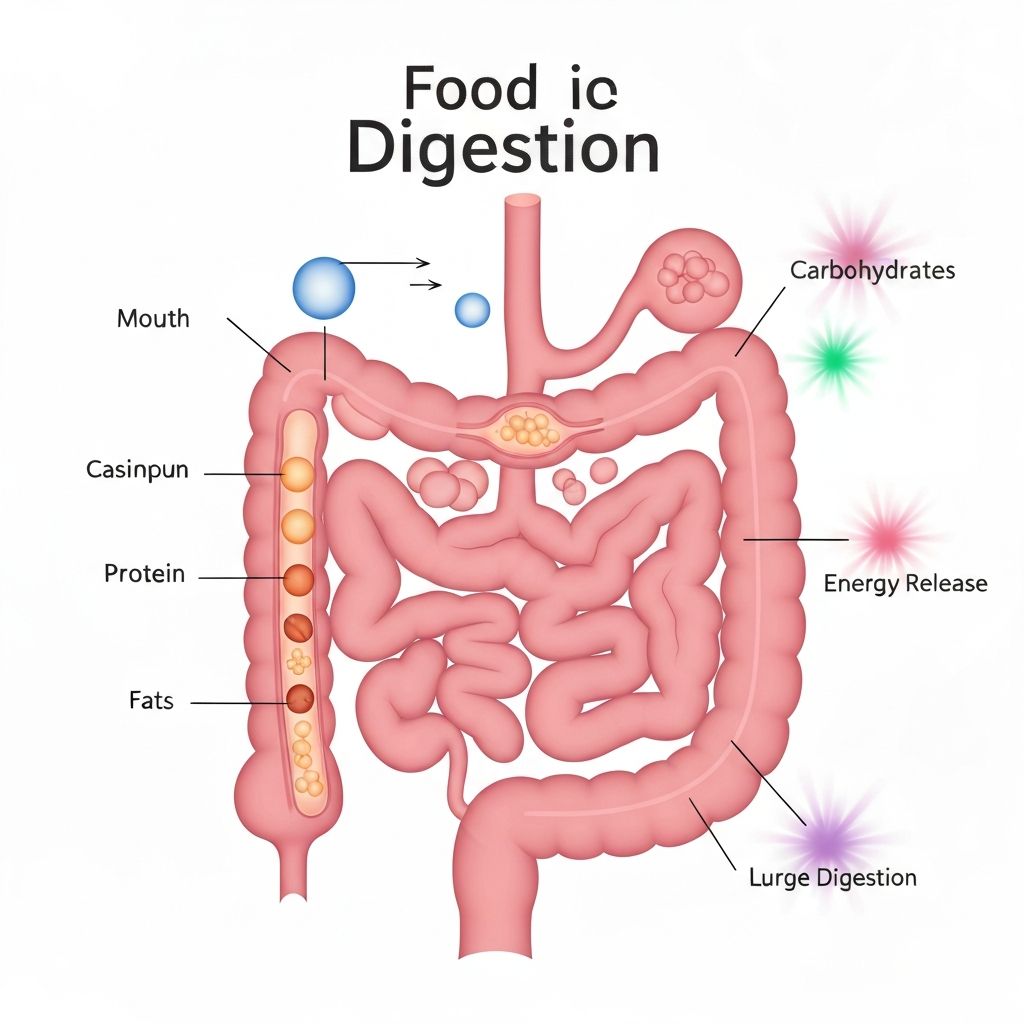

The Digestion and Absorption Process

Digestion involves multiple sequential steps requiring energy expenditure:

- Mechanical digestion: Your mouth and stomach mechanically break down food using muscle contractions (mastication and peristalsis), requiring muscular energy

- Chemical digestion: Enzymes in saliva, stomach, and intestines break down macronutrients into absorbable components; enzyme production and function require energy

- Absorption: Nutrient absorption across the intestinal wall often requires active transport, which demands cellular energy (ATP)

- Transportation: Absorbed nutrients are transported via the bloodstream; this physiological transport requires energy

- Storage and processing: Nutrients are processed, stored, or used by cells, processes that require energy investment

Thermic Effect by Macronutrient

Different macronutrients require different amounts of energy for digestion and processing:

Carbohydrates

Require approximately 5-10% of their calories for digestion and processing. This is the lowest thermic effect among macronutrients. Carbohydrates are broken down into simple sugars relatively efficiently and absorbed readily by the intestine.

Proteins

Require approximately 20-30% of their calories for digestion and processing, significantly higher than carbohydrates. Proteins must be broken into amino acids through enzyme action, and amino acids undergo complex metabolic transformations that demand substantial energy investment.

Fats

Require approximately 0-3% of their calories for digestion and processing, the lowest among macronutrients. Despite being energy-dense and requiring emulsification for absorption, fats have minimal thermic effect relative to other nutrients.

Factors Affecting Thermic Effect

Several factors influence the magnitude of TEF:

- Meal macronutrient composition: Protein-rich meals produce greater thermic effect than carbohydrate or fat-rich meals of equivalent energy

- Meal size: Larger meals generally produce greater absolute thermic effect, though proportionally the effect remains similar

- Meal composition complexity: Whole foods and complex meals may require more processing energy than simple refined foods

- Physical fitness: Some research suggests fitness level may modestly influence thermic response, though findings are inconsistent

- Insulin sensitivity: Individuals with better insulin sensitivity may have different thermic responses

- Individual variation: Genetic and metabolic factors create substantial variation in thermic response between individuals

Practical Implications

While the thermic effect of food is real and measurable, its practical implications for overall energy balance are often overstated. Even consuming a very high-protein diet producing the maximum thermic effect difference would result in only modest differences in total daily energy expenditure compared to other dietary approaches.

The thermic effect should be considered within the broader context of overall energy balance rather than as a primary driver of weight changes. Total energy intake and overall energy expenditure remain the fundamental determinants of energy balance, with TEF playing a supporting role.

Historical Research on TEF

Scientific understanding of dietary thermogenesis developed gradually:

Researchers noted that food consumption increased body temperature and heat production, though mechanisms remained poorly understood.

Calorimetry experiments quantified the increase in energy expenditure following food consumption, establishing thermic effect as a measurable phenomenon.

Systematic research established differential thermic effects of different macronutrients, with proteins producing the greatest effect.

Contemporary research elucidates biochemical mechanisms underlying thermic effects, including ATP utilisation, enzyme synthesis, and nutrient transport processes.

TEF and Energy Balance Context

Understanding TEF provides valuable insight into how energy expenditure operates, but perspective is essential. While protein consumption requires more energy for processing than carbohydrate or fat consumption, the absolute difference in total daily expenditure from macronutrient composition variations is relatively small compared to differences in physical activity or individual metabolic variation.

TEF demonstrates that all food is not processed identically by the body and that nutrient type influences physiological processes. This foundational knowledge contributes to comprehensive understanding of energy balance without suggesting that thermic effect is a primary determinant of body weight changes.